| ANALYSIS By Richard Black Environment correspondent, BBC News website |

Not the words of a environmental campaigner or a frustrated climate scientist, but the plain assessment from Britain's Environment Secretary David Miliband as the 2006 round of United Nations climate negotiations whimpered to a close.

But environmental campaigners obviously agreed. Some groups even began direct action during the year, something which has traditionally been associated with a completely different power source, nuclear fission.

Coal-fired power stations in the UK, including Europe's biggest, Drax, were blockaded and attempts made to occupy them.

Tens, probably hundreds of thousands marched on a co-ordinated day of action in November.

Musicians and actors joined the fray, as they did on poverty 20 years ago.

Climate change has started to become a popular cause.

Ups and downs

Their argument is simply that the world's political leaders are failing to take the scientific evidence seriously.

As represented most importantly by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the consensus suggests that global emissions of greenhouse gases need to fall by about 60% on a timescale of a few decades in order to be sure that the most graphic of climate consequences are averted.

Yet at the end of the year, the trend was pointing in the opposite direction.

The rate of emissions growth for carbon dioxide, the most important gas in the man-made greenhouse, is increasing; a decade ago emissions were climbing by less than 1% per year, now the rate is above 2% per year.

"The [greenhouse gas] concentrations in the atmosphere are going up, so it hasn't been a year of success in terms of having an impact on this process," observes Jonathan Lash, president of the World Resources Institute, an environmental think-tank based in Washington DC.

"We have world leaders who say they're committed; but there's a long distance between saying you're committed and making the actual changes in the factories and power plants and automobiles that create the emissions; and that process is still moving very slowly."

Off target

The UN talks in Nairobi ended with no deal on targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions when the current Kyoto Protocol quotas expire in 2012, and no firm timetable for agreeing such targets.

Whether the UN process can ever deliver further cuts is an open question. In order to get the juggernaut of Kyoto procedures pointing in a new direction by 2012, targets need to be tied up perhaps two years, perhaps three years before that.

The European Union is publicly committed to a new round of targets.

But some member states are a world away from meeting their existing ones; and even as delegates were boarding the planes to Nairobi, many EU governments submitted plans for the second phase of the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) which would have raised their emissions, not cut them, in the years running up to 2012.

What of the other processes which have sprung up in the last two years with the declared intention of turning the rising tide of emissions?

The Asia-Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate brings together six countries whose emissions account for roughly half the global total - Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and the US - in a pact which aims to reduce emissions by assisting the private sector to create clean technologies and transfer them to developing countries.

It held its first ministerial meeting in Sydney in January. I have rarely seen a room-full of journalists as stunned as the group there were, as US energy secretary Samuel Bodman told us that private companies will solve climate change because the people in charge of them care.

"I believe that the people who run the private sector, who run these companies - they too have children, they too have grandchildren, they too live and breathe in the world, and they would like things dealt with effectively; and that's what this is all about," he said.

The single word "Enron" traversed a hundred brains.

According to an Australian Government report commissioned for the Sydney meeting, the Partnership does not in fact expect to cut global greenhouse gas emissions - it expects them to double over the next 50 years, even if all its projects come to fruition.

There were already suspicions in the NGO community that the Partnership was really about trade, not climate. Since the Sydney meeting we have seen two major deals tied up between members which will see the US export nuclear technology to India, and Australia export uranium to China.

Let us fast forward then to Monterrey in Mexico, and the second ministerial session of the Dialogue on Climate Change, Clean Energy and Sustainable Development, which brings the G8 countries together with major developing nations including Brazil, China, and India.

The conclusions of this potentially very powerful group were that climate change is really serious, we need to do something, but we are not making any firm commitments now.

That might have a familiar feel by now.

Costing the Earth

Two other initiatives burst on to the global stage during 2006; one, a movie from a former politician, the other a weighty report from a leading economist.

Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth is a masterpiece of communication - wherever you stand on climate science, to make it engaging for an hour and a half is surely some feat. As a tool to change policies, however, its value must be doubtful, as it is largely the converted that will see it.

Sir Nicholas Stern's review of climate change economics should hit a little harder. Certainly Tony Blair thought so, commenting: "It proves tackling climate change is in fact a pro-growth strategy.

"It shows that if we fail to act, the cost of tackling the disruption to people and economies would cost at least 5%, on the worst case scenario as much as 20%, of the world's output. In contrast, the cost of action to halt and reverse climate change would cost just 1%."

As the year ended, Mr Blair's government was, by his own logic, deciding to risk growth by approving expansion plans for major airports.

Sir Nicholas took his review on a tour of world capitals. But even as he breakfasted with officials in Beijing and Delhi, a report from the Asian Development Bank warned that Asia's emissions will triple over the next 25 years.

Boxing clever

The single biggest obstacle to progress in negotiations has been the reluctance of the US to engage and to accept that the international community has any right to restrict its emissions.

But signs emerged that something was changing in Washington with the mid-term elections in November, which returned the Democrats to power in both houses of Congress.

Jonathan Lash believes this is already having an impact on how climate issues are debated.

"Now the chair will be Senator Boxer, who has already committed herself to very strong legislation making mandatory reductions. We'll see the same kind of shift in the House of Representatives; so we're going to see the leadership pushing ahead instead of setting up obstacles."

Below the federal level, states and cities are also pressing ahead with various initiatives, laws and measures on emissions caps, carbon trading, energy efficiency and carbon burial.

None of this is likely to change the US stance in international negotiations, though rumours persist in Washington that President Bush may announce some new measures during his next State of the Union address.

Heated debate

Of course, not everyone is convinced by the scientific arguments of the IPCC or the economic ones of Sir Nicholas Stern.

The diverse community of "climate sceptics" were visible and vocal during 2006, and registered at least one blow for an alternative way of explaining global warming when a Danish research group showed in a laboratory experiment that highly energetic particles could enhance the formation of water droplets in air.

A number of economists lined up to dispute the Stern Review's methods and conclusions. These voices will surely remain vocal as 2006 turns into 2007.

But shouting loudest of all next year will be the Fourth Assessment Report from the IPCC. It will have been five years in the making, and will present the current consensus on climate science, on impacts and costs, as determined by its committees of experts.

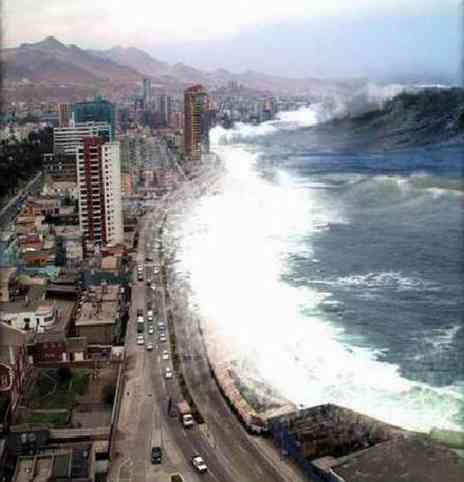

Its headline projections are expected to differ little from those contained in its last report, issued in 2001; rising temperatures, rising sea levels, and major specific impacts such as the irreversible drying out of the Amazon.

Once again we will hear demands from climatologists to keyboard players, from theoretical physicists to thespians, for more action.

Perhaps we will get it. But the omens are not promising.

Richard.Black-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk