Apocalypse now: how mankind is sleepwalking to the end of the Earth

Floods, storms and droughts. Melting Arctic ice, shrinking glaciers, oceans turning to acid. The world's top scientists warned last week that dangerous climate change is taking place today, not the day after tomorrow. You don't believe it? Then, says Geoffrey Lean, read this...

06 February 2005

Future historians, looking back from a much hotter and less hospitable world, are likely to play special attention to the first few weeks of 2005. As they puzzle over how a whole generation could have sleepwalked into disaster - destroying the climate that has allowed human civilisation to flourish over the past 11,000 years - they may well identify the past weeks as the time when the last alarms sounded.

Last week, 200 of the world's leading climate scientists - meeting at Tony Blair's request at the Met Office's new headquarters at Exeter - issued the most urgent warning to date that dangerous climate change is taking place, and that time is running out.

Next week the Kyoto Protocol, the international treaty that tries to control global warming, comes into force after a seven-year delay. But it is clear that the protocol does not go nearly far enough.

The alarms have been going off since the beginning of one of the warmest Januaries on record. First, Dr Rajendra Pachauri - chairman of the official Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) - told a UN conference in

Then the biggest-ever study of climate change, based at

Finally, the

But it was last week at the Met Office's futuristic glass headquarters, incongruously set in a dreary industrial estate on the outskirts of

The conference opened with the Secretary of State for the Environment, Margaret Beckett, warning that "a significant impact" from global warming "is already inevitable". It continued with presentations from top scientists and economists from every continent. These showed that some dangerous climate change was already taking place and that catastrophic events once thought highly improbable were now seen as likely (see panel). Avoiding the worst was technically simple and economically cheap, they said, provided that governments could be persuaded to take immediate action.

About halfway through I realised that I had been here before. In the summer of 1986 the world's leading nuclear experts gathered in

It was all, of course, much less dramatic at

I am willing to bet there were few in the room who did not sense their children or grandchildren standing invisibly at their shoulders. The conference formally concluded that climate change was "already occurring" and that "in many cases the risks are more serious than previously thought". But the cautious scientific language scarcely does justice to the sense of the meeting.

We learned that glaciers are shrinking around the world. Arctic sea ice has lost almost half its thickness in recent decades. Natural disasters are increasing rapidly around the world. Those caused by the weather - such as droughts, storms, and floods - are rising three times faster than those - such as earthquakes - that are not.

We learned that bird populations in the

Worse, leading scientists warned of catastrophic changes that once they had dismissed as "improbable". The meeting was particularly alarmed by powerful evidence, first reported in The Independent on Sunday last July, that the oceans are slowly turning acid, threatening all marine life (see panel).

Professor Chris Rapley, director of the British Antarctic Survey, presented new evidence that the West Antarctic ice sheet is beginning to melt, threatening eventually to raise sea levels by 15ft: 90 per cent of the world's people live near current sea levels. Recalling that the IPCC's last report had called

Professor Mike Schlesinger, of the

The experts at

Now a new scientific consensus is emerging - that the warming must be kept below an average increase of two degrees centigrade if catastrophe is to be avoided. This almost certainly involves keeping concentrations of carbon dioxide, the main cause of climate change, below 400 parts per million.

Unfortunately we are almost there, with concentrations exceeding 370ppm and rising, but experts at the conference concluded that we could go briefly above the danger level so long as we brought it down rapidly afterwards. They added that this would involve the world reducing emissions by 50 per cent by 2050 - and rich countries cutting theirs by 30 per cent by 2020.

Economists stressed there is little time for delay. If action is put off for a decade, it will need to be twice as radical; if it has to wait 20 years, it will cost between three and seven times as much.

The good news is that it can be done with existing technology, by cutting energy waste, expanding the use of renewable sources, growing trees and crops (which remove carbon dioxide from the air) to turn into fuel, capturing the gas before it is released from power stations, and - maybe - using more nuclear energy.

The better news is that it would not cost much: one estimate suggested the cost would be about 1 per cent of Europe's GNP spread over 20 years; another suggested it meant postponing an expected fivefold increase in world wealth by just two years. Many experts believe combatting global warming would increase prosperity, by bringing in new technologies.

The big question is whether governments will act. President Bush's opposition to international action remains the greatest obstacle. Tony Blair, by almost universal agreement, remains the leader with the best chance of persuading him to change his mind.

But so far the Prime Minister has been more influenced by the President than the other way round. He appears to be moving away from fighting for the pollution reductions needed in favour of agreeing on a vague pledge to bring in new technologies sometime in the future.

By then it will be too late. And our children and grandchildren will wonder - as we do in surveying, for example, the drift into the First World War - "how on earth could they be so blind?"

WATER WARS

What could happen? Wars break out over diminishing water resources as populations grow and rains fail.

How would this come about? Over 25 per cent more people than at present are expected to live in countries where water is scarce in the future, and global warming will make it worse.

How likely is it? Former UN chief Boutros Boutros-Ghali has long said that the next

DISAPPEARING NATIONS

What could happen? Low-lying island such as the

How would this come about? As the world heats up, sea levels are rising, partly because glaciers are melting, and partly because the water in the oceans expands as it gets warmer.

How likely is it? Inevitable. Even if global warming stopped today, the seas would continue to rise for centuries. Some small islands have already sunk for ever. A year ago,

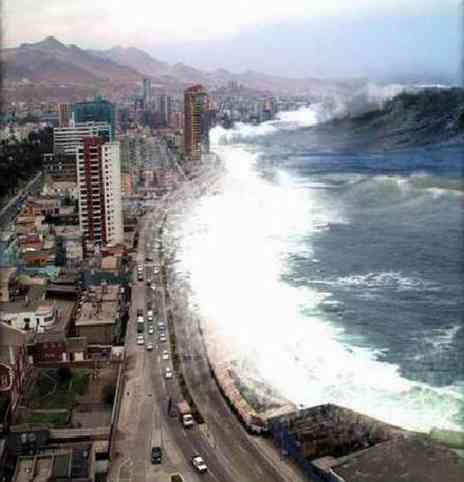

FLOODING

What could happen?

How would this come about? Ice caps in Greenland and

How likely is it? Scientists used to think it unlikely, but this year reported that the melting of both ice caps had begun. It will take hundreds of years, however, for the seas to rise that much.

UNINHABITABLE EARTH

What could happen? Global warming escalates to the point where the world's whole climate abruptly switches, turning it permanently into a much hotter and less hospitable planet.

How would this come about? A process involving "positive feedback" causes the warming to fuel itself, until it reaches a point that finally tips the climate pattern over.

How likely is it? Abrupt flips have happened in the prehistoric past. Scientists believe this is unlikely, at least in the foreseeable future, but increasingly they are refusing to rule it out.

RAINFOREST FIRES

What could happen? Famously wet tropical forests, such as those in the Amazon, go up in flames, destroying the world's richest wildlife habitats and releasing vast amounts of carbon dioxide to speed global warming.

How would this come about?

How likely is it? Very, if the predictions turn out to be right. Already there have been massive forest fires in Borneo and

THE BIG FREEZE

What could happen?

How would this come about? Melting polar ice sends fresh water into the

How likely is it? About

evens for a Gulf Steam failure this century, said scientists last week.

STARVATION

What could happen? Food production collapses in

How would this come about? Rainfall is expected to decrease by up to 60 per cent in winter and 30 per cent in summer in southern

How likely is it? Pretty likely unless the world tackles both global warming and

ACID OCEANS

What could happen? The seas will gradually turn more and more acid. Coral reefs, shellfish and plankton, on which all life depends, will die off. Much of the life of the oceans will become extinct.

How would this come about? The oceans have absorbed half the carbon dioxide, the main cause of global warming, so far emitted by humanity. This forms dilute carbonic acid, which attacks corals and shells.

How likely is it? It is already starting. Scientists warn that the chemistry of the oceans is changing in ways unprecedented for 20 million years. Some predict that the world's coral reefs will die within 35 years.

DISEASE

What could happen? Malaria - which kills two million people worldwide every year - reaches

How would this come about? Four of our 40 mosquito species can carry the disease, and hundreds of travellers return with it annually. The insects breed faster, and feed more, in warmer temperatures.

How likely is it? A Department of Health study has suggested it may happen by 2050: the Environment Agency has mentioned 2020. Some experts say it is miraculous that it has not happened already.

HURRICANES

What could happen? Hurricanes, typhoons and violent storms proliferate, grow even fiercer, and hit new areas. Last September's repeated battering of

How would this come about? The storms gather their energy from warm seas, and so, as oceans heat up, fiercer ones occur and threaten areas where at present the seas are too cool for such weather.

How likely is it? Scientists are divided over whether storms will get more frequent and whether the process has already begun.

No comments:

Post a Comment